Not just "ephemeral creatures living on an insignificant spot"

Working with me in therapy often includes discussion of existential issues like what this post talks about. It can be hard to find a therapist who can engage with you on deep issues and get closer to big questions. If this resonates with you, call me today for an appointment: 917-873-0292.

A celebrated psychoanalyst named Wilfred Bion (1897-1979) opined:

We are, after all, ephemeral creatures living on an insignificant spot of earth that circles (according to the astronomers) round an ordinary star occupying a somewhat peripheral position in a particular nebula. So the idea that the universe obeys the laws in such a way that it becomes comprehensible to us is sheer nonsense; it seems to me to be an expression of omnipotence or omniscience (7/4/1977, Tavistock Seminars, p. 28).

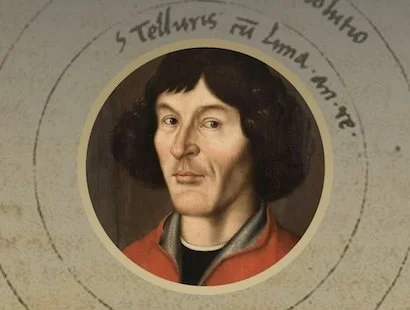

This idea is intended to be refreshing—like Socrates’ inconvenient reminders that humans know nothing compared to the Gods—-and to wake us from the trance of our daily affairs. But suppose we have heard this before. Suppose it has not had the intended liberating effect, but has become a reach for power, whereby we in the audience are supposedly hypnotized by commerce and culture (Wordsworth’s “getting and spending”), whereas Bion and others like him are awake. It’s as if Bion thinks this is news to us; that we have been lingering in the medieval past, waiting for a Copernicus to set us free. Announcing that humans live “on an insignificant spot” is, I suggest, “an expression of omnipotence or omniscience.”

All of the “significance” or “meaning” to which we have any access is centered here, on the only green world we know. “Earth’s the place for love,” wrote Robert Frost, “I don’t know where it’s likely to go better.” When Socrates reported that the Delphic Oracle had said “No human being is wiser than Socrates,” it was clear that Apollo meant human wisdom is worthless compared to the wisdom of the Gods. To get exuberant about the “vastness of human ignorance,” as Bion and others have done so often, is an expression of omniscience which pretends to have exited from that state and looked back on it with fond pity—as if the whole life of mankind were a provincial illusion, except for this very humble bit of it where a thinker notices the surrounding universe. Experience says that our “merely” human action creates real relationships, real suffering and losses, real nurturance, connection and love, creativity and damage, joy and pain. Of course the scale of our actions is a match for our own size and longevity, not those of a galaxy or a mouse.

When people play this “human insignificance” card, or sagely announce that all people are somehow 100% ignorant, or that life is meaningless—just ask them: compared to what?

They are adopting a stance, making a gesture, offering a corrective to somebody’s dogmatic slumber. But no matter how often they adopt a Socratic pose, they still conduct their own affairs as if those were plenty significant to them, because making meaning is what human beings do. Socrates himself claimed to know nothing, but he introduced that speech (his courtroom oration in his own defense) with very little doubt: πιστεύω γὰρ δίκαια εἶναι ἃ λέγω. “For I am confident that what I say is just.”

Since we ephemeral creatures acquired, say, the Pythagorean theorem, and that theorem is not nothing, human beings do know something. We don’t know what the Gods know, or what the unconscious knows, or what another person knows of their own body and life experience—but we do know something. We are tiny compared with a whale, and huge compared with a fly—not merely tiny-compared-to-anything. It is, perhaps, “sheer nonsense” to speak as if the telescope has been invented, but the microscope has not. If human beings are “insignificant,” then what is significant? And to whom?

Perhaps this impulse—to lament our utter insignificance, our total ignorance, our ephemeral brevity, our powerlessness in a cold universe—is an unconscious repetition of very early feelings. A baby, after all, is overwhelmingly lacking in power, knowledge, size, and ability compared to the adult(s) on whom the baby is totally dependent. Similarly, a grownup’s grandiose disillusion with all of human culture echoes the teenager’s outraged discovery that our lives are mediated by socially constructed stuff, not eternal verities. The parents who once seemed all-knowing and all-powerful are deflated in our estimation, an experience that gets repeated in other domains later on.

Followers of psychoanalytic mystical monists like Bion and Jung and Lacan often need reminding: it is hubristic to boast of one’s own humility, intellectual or otherwise. The young Martin Luther was praying in his cell one day, whipping himself in his ascetic devotions, when the Devil appeared to him, saying: “Very good, Martin. Soon you’ll be more pious than God.” The cure, it seems, is to accept that everything contains a seed of its opposite; that altruism need not be “pure,” or else it may never happen; and that meaning is its own reward, neither absolute nor entirely empty. “Ephemeral” in Ancient Greek means “of a day.” We are indeed fleeting, temporary, evanescent. A day is an instant for a mountain—a lifetime for a mayfly, an aeon for an evanescent neutrino; and for a timeless photon, eternity. But we are not mountains, nor may-flies. Your life is meaningful, because meaning can only happen in a life, just as location can only happen in the universe. Life is meaning.

Working with me in therapy often includes existential issues like what this post talks about. It can be hard to find a therapist who can engage with you on deep issues and help you orient yourself to big questions. If this resonates with you, you can call me today for an appointment: 917-873-0292.